Beware the Peace Dividend

There is much talk of a possible peace-dividend for Australia with operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, East-Timor and the Solomon Islands concluded or drawing to a close. This is not the first time that a government has bid farewell to arms and found a soft source of cash to fund elsewhere. The Australian Defence Force should also beware of preparing for peace-keeping operations at the expense of maintaining its more serious capabilities based on the British Army’s fall from grace…

By November 1918, the British Army was amongst the most modern in the world yet by 1939 it suffered from qualitative inferiority in equipment, training and tactics. How could the victors of Amiens and Cambrai find themselves stranded on the beaches of Dunkirk, outmanoeuvred, out-gunned and out-thought?

By the end of ‘The War To End All Wars’, Britain’s strategic priorities shifted from defence to domestic matters, a change that would not affect all three services equally.[1] The Royal Navy (RN) and the Royal Air Force (RAF) argued that they could meet the government’s three objectives for the military:[2] to protect the empire, deter attacks and insurance, i.e. readiness to defend British interests if deterrence failed.[3]Both services aggressively advocated a policy of substitution, using technological advancement to reduce the financial and labour costs of defence. The RAF persuaded Cabinet[4] that it could conduct cost-effective colonial policing in Iraq[5] and elsewhere[6] while protecting Britain and her interests from attack,[7]seeing these priorities as complementary, an argument which the Army struggled to match.

The Army could not reconcile deterrence and insurance with the smaller, lighter force that the government sought for colonial policing. The head of the Army wrote in 1921 that

The War Office is… greatly handicapped compared to the Navy who have always had a 2-power standard [or similar]. Soldiers have no standard…therefore the unfortunate war office is given an instrument which has no relation to any known or unknown war, has no standard up to which to work[sic] and then is asked to make plans.[8]

Primary sources and contemporary accounts challenge the myth that that the Army failed to modernise because it sought to return to ‘proper soldiering’ on the frontiers. The General Staff were generally ambivalent about imperial intervention operations, believing that they inevitably became longer and costlier than planned.[9] Instead, Army policy to prepare for a large continental war was consistent, and consistently frustrated, between the wars. As early as 1920, the Army sought to establish an Experimental Mechanised Force (EMF)[10]to learn how to integrate tanks and infantry[11] with the intention of mechanising most of the Army by 1930.[12]Whilst these plans were delayed for seven years by operational commitments and the Government’s insistence that new forces be offset by larger cuts in existing formations, the interwar Chiefs of the Imperial General Staff(CIGS) persisted with this policy even at the risk of dismissal.[13]The loss of strategic influence would also manifest itself in shrinking budgets and the use of the Treasury to restrict the Army’s strategic options.

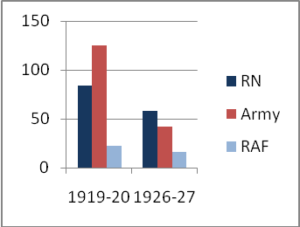

In contrast to the Army, inter-war naval budgets were heavily sequestered due to the RN’s compelling strategic narrative, the significant fixed costs of warships and centuries of maritime tradition. This policy meant that, although all service budgets shrank (Figure 1),the Army came out the greatest loser of all while shouldering the bulk of operations (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1. Defence Budgets (net) in millions of GBP[14]

Defence Budgets (net) in millions of GBP

Not only would Army finances decline but, due to a reputation for poor financial management,[15] it would lose control of its budget to civil servants leading to damaging cuts in development.[16] A cautionary tale for the ADF in and of itself!

Treasury wielded both administrative and budgetary influence over the Army to a greater degree than the other services and ruthlessly used this power to enforce compliance with strategic policy. This constraint had significant impacts on interwar capability developments, including the qualitative inferiority of British tanks. In 1932, the Treasury ended funding for medium tank research and development, forcing the Army’s Director of Modernisation to terminate the development of medium tank engines.[17]Consequently, the development of engines, and the capacity of the defence industry to manufacture them, effectively ceased. British tanks would suffer from underpowered, unreliable and flammable engines; in North Africa, the Royal Tank Regiment lost more tanks to mechanical failures than to enemy action.[18]

In addition to research and development, Treasury’s narrow strategic focus also prevented trials of new force structures. The EMF, which was finally created in 1927, was terminated abruptly by the Treasury after only 23 months in order to divert funds to other, conventional units. Undeterred, the War Ministry continued with attempts to modernise the Army. In 1934,[19] CIGS Montgomery-Massingberd proposed a successor to the EMF, this time a mobile division.[20]Again the greatest impediment to this progressive plan was Treasury. Funding was not approved for creation of the Division until mid-1937, by which time it was too late to develop doctrine, train the force and manufacture mechanised vehicles. Whilst the eventual structure of the Division has been criticised, that critique misses the essential point. Its existence, like that of the EMF, was the sine qua non for the development of combined arms force structure and tactics. The General Staff produced sophisticated doctrine throughout the inter-war period but had neither the troops nor the opportunity to test and refine it. This is not to suggest that, had the EMF been retained or the Mobile Division raised in 1934, the Army would have matched German levels of combined arms tactics. Without armoured vehicles and armoured formations, though, British mechanised theory remained just that.

The Army also contributed to its own financial woes. Firstly, it insisted on across-the-board cuts rather than making hard decisions to disestablish certain units or capabilities. ‘I am cutting in all directions so as to keep the little Army at its present size’, one CIGS wrote.[21] Venerable but anachronistic organisations were preserved at the expense of the modern formations the Army Chiefs desperately wanted. Secondly, the Army had long recognised that its regular forces could become so occupied by imperial duties that it struggled to maintain the skills to fight large, conventional wars. Consequently, a large strategic reserve, the Territorial Army (TA), had been maintained to preserve conventional war-fighting skillsand provide an experienced cadre if the Army needed to rapidly expand. In an attempt to find budget savings the Army would critically undermine this strategic reserve.

While the TA accounted for only 15% of the Army’s budget, the General Staff considered it discretionary spending, i.e. whilst no economies could be made from a regular soldier’s salary, territorials were only paid for attendance. Reducing the amount of training they conducted yielded savings. Compounding this, the planned modernisation of the TA was never carried out, deferred from one budget crisis to the next.[22]Therefore, when war was declared, the Army had to re-live the experience of 1914 and, without ever having conducted adequate collective or staff training, raise an expeditionary force from scratch.[23]This neglect also ignored the TA’s potential as an interim, experimental force to act as a low-cost alternative to regular forces. These issues were not uniquely British, but unlike most other nations, the British Army experienced a consistently high operational tempo in the inter-war period.

When combined with a strategic disconnect and severe budget cuts, the Army’s high operational tempo would have a serious impact on both collective training and equipment design. At the same time that the British Army suppressed five significant insurgencies[24]and fought in two ‘small wars’,[25]the General Staff would focus on the development of surprisingly advanced tactical doctrine.[26]This doctrine focussed on fighting a complex war against a large, sophisticated opponent but without training opportunities, modern doctrine alone could not transform a force. Commanders had to prioritise training for the small wars of today at the expense of the potential large war of tomorrow. Consequently, British soldiers excelled in small-group, counterinsurgency and policing tactics but rarely trained against a comparable adversary. In addition to tempo, colonial commitments also meant that the Army was too thinly spread to train for a major war.

At any one time between 1919 and 1937, approximately half the Army was posted in small garrisons around the globe.[27] The Army simply lacked the manpower to meet its current commitments and conduct large-scale modernisation. It was infeasible to modernise units before a rotation during which they might spend up to six years in a remote corner of the empire where they neither needed nor could maintain a mechanised fleet. Whilst the Army’s decentralised, regional command structure made it agile and responsive to local demands, it retarded the rapid propagation of ideas and doctrine. Most importantly, it denied the Army the ability to train on anything approaching the scale the German Army achieved.

During the entire inter-war period, the British Army managed to conduct only two Corps-level exercises and none as an Army Group, a regular feature of continental training.[28]Frequent security and stabilisation operations interfered with major training activities. In 1921, Divisional manoeuvres designed to build on the lessons of the Hundred Days campaign were aborted due to a deployment to Turkey. As late as 1937, a planned Corps Exercise was cancelled[29] due to the need to deploy the 1st and 4th Divisions to Palestine. The exigencies of colonial operations did more than hamper collective training and the development of doctrine; they also contributed to the Army’s materiel inferiority.

Meeting the demands of colonial and counter-insurgency operations entailed compromises in firepower and technical sophistication that affected all levels of land materiel. The nature of these operations demanded robust, easily portable equipment that imposed the minimum burden on resupply. Given these considerations, the Army decided not to upgrade to semi-automatic rifles,[30]sub-machine guns and belt-fed section machine guns,[31] leaving the infantry outgunned by its peers. Colonial policing against a lightly armed enemy also resulted in assigning low priority to the development of anti-aircraft (AAA) and anti-tank artillery (AT).

For example, the WWI-era QF3.6 was approved for replacement in 1928, but funding its replacement was not considered a priority until 1934, with production not commencing until 1937.[32]Consequently, the Army had fewer than 500 heavy pieces of AAA at the start of the war. During the combined air and ground assault in France and North Africa, the Army was heavily outgunned. Whilst the Wehrmacht actually had fewer tanks than the Allies during the Battle of France, it used anti-tank guns to generate local superiority over Allied forces.[33]The British Army could not match this capability numerically or qualitatively until 1942–3.

Likewise the 25-pounder field gun adopted in 1937 as the Army’s principal piece of field artillery was reliable, robust, easy to transport and effective against infantry in the open. To achieve lightness and sea-transportability, though, it sacrificed shell weight, significantly lessening its effectiveness against armour and entrenched infantry compared to the French and German equivalents.[34]Contemporary operations also influenced the development of British armour which, already hampered by poor engines, incorporated low-velocity, rapid-firing guns that were suitable for attacking infantry in the open but lacked penetration against German Panzers.[35] The effects of colonial requirements, and a lack of large manoeuvres, would also mask weaknesses in command and control systems.

One of the less obvious reasons why the German Army outmanoeuvred the British in their early encounters was its adaptability, underpinned by the comprehensive communications systems of its armoured fighting and command vehicles. The need for this type of command-and-control system became evident only when conducting large-scale training exercises against a capable opposing force,[36]something that the British Army never achieved between the wars. The development of communications systems had been one of the main but unfulfilled priorities of the short-lived EMF, just one consequence amongst many of misallocated funding priorities combined with the demands of colonial policing.

The real failure of the Army Staff was not an inability to anticipate the likelihood or nature of a future continental conflict, this they had foreseen with striking prescience decades earlier. Instead the Army was never able to reconcile its strategic aspirations with government policy, in the process losing control over force structure and posture.

Without large-scale training and modern force structures with which to test doctrine and people, these other weaknesses could not be identified and remedied.

The issues facing the inter-war British Army—the conclusion of a major conflict; de-prioritisation of defence; severe budget cuts and frequent peace-keeping operations—are those facing western Armies in 2013.

Bitter experience reveals that the ‘peace-dividend’ is rarely worth the repayments, something worth remembering by Australian strategic planners.

[1] Whilst some historians refer to the so-called policy of the ‘ten year rule’, most contemporary Cabinet papers are vague about this length of time and instead speak of a lower risk period of five to ten years. The Treasury may in fact have adopted a ‘ten-year’ policy long before the Cabinet. See Cabinet Papers cited in bibliography 1919–27.

[2] These objectives were developed by the Foreign Office and discussed by the Chiefs of Staff Committee throughout the 1920s. See Committee of Imperial Defence: Chiefs of Staff Committee: Minutes and Memoranda, CAB 53 and COS 36, CAB 55/12.

[3]John Ferris, The Evolution of British Strategic Policy 1919-26(London: MacMillan, 1989, p. 39).

[4]Memorandum by the Chief of the Air Staff on the Air Force Scheme of Control in Mesopotamia CP. 3197, in Cabinet Conclusion 5. Mesopotamia. 18 August 1921.

[5]Cabinet Conclusion 2.Iraq. 18 December 1925.

[6]Cabinet Memorandum. Principles to be adopted in flying on the frontier. 15 October 1925.

[7] Sir Hugh Trenchard to Sir Winston Churchill, 11 January 1921, AIR 5/552 in Ferris (1989),p. 84.

[8] Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), effectively chief of the Army, Sir Henry Wilson writing to GOC Aldershot Command (Commander Home Forces) General Rawlinson, 6 July 1921, Wilson Papers 73/1/9/13 D in Ferris (1989) p. 78.

[9] The CIGS Sir Henry Wilson notoriously wrote, ‘the habit of interfering with other people’s business and making “peace” is like buggery: once you take to it you cannot stop’. Private letter from Wilson to Charles Sackville-West (Military Attaché to Paris), 11 August 1921 (Wilson Papers, HHQ 2/12G/50) in Jeffrey (2008), 234.

[10]An embryonic combined-arms, brigade-sized organisation.

[11] A great criticism of British tactics at the start of WWII was the lack of tank-infantry integration compared to the Germans, but such separation was not consistent with General Staff doctrine.

[12] First conceived by Master General of Ordnance General Furze, the force was enthusiastically supported by CIGS Wilson and championed by Deputy-CIGS Chetwode. See Minutes Army Council Meeting 28 November 1919 War Office Archives 163/24 and Letter from Chetwode to Montgomery-Massingberd, 13 Dec 1920, Montgomery-Massingberd papers vol. 122. In Ferris (1989) p. 70.

[13] General Cyril Deverell was dismissed in 1937 by Secretary of State for War Leslie Hore-Belisha for his views.

[14] British Treasury Service Estimates, cited in in Ferris (1989) Appendix 1.

[15]This was due to a number of costly and fruitless projects, such as the medium D tank, a habit of wilfully exceeding its annual budget and routinely circumventing Cabinet approval for procurement. See 19th Finance Committee of Cabinet meeting, 09 February 1920 Cabinet papers 385, CAB 24/97

[16] For example, the Geddes Review (popularly known as the Geddes-Axe) of government expenditures dictated which formations and capabilities would be pursued, not the General Staff. (Henry Higgs, ‘The Geddes Reports and the Budget’, The Economic Journal, 32:126(June 1922): 252.

[17]Chief of the General Staff minute to Secretary of State 09 October 1936 cited in French (2006).

[18]Crow (1972).

[19]CIGS Minute 1, 15 October 1934 PRO/WO 32/2847 in Harris (1995).

[20] The Mobile Division was in fact an armoured division comprised of tanks, armoured reconnaissance and mechanised infantry. The original plans included two motorised artillery brigades and mechanised engineers, but neither the equipment nor the funding to design it was made available.

[21] Letter from CIGS Lord Cavan to General Godley (GOC Southern Command) written in 1924, Alexander Godley Papers, Series 3

[22] M.C. Eden, ‘The Organisation and Training of Territorial Army Units’, Journal of the Royal United Service Institute, 84 (1939): 135-43.

[23] For an example of the differences between experienced, regular troops and inexperienced, new soldiers, compare the superior performance of the 7th Armoured Division in North Africa with that of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) during the battle of France. See John Keegan, ed., Churchill’s Generals(London: Cassell Military, 2005).

[24]Egypt 1919, Ireland 1919–21, Iraq 1920, Palestine 1929 and again in 1936–39. See Anthony Clayton, The British Empire as a Superpower(London: MacMillan, 1986).

[25] Afghanistan 1919 and Turkey 1919–22.See Clayton (1986).

[26] The 1929 edition of Field Service Regulations (Organisation and Administration) devotes 11 of its 12 chapters to a ‘war of the first magnitude’ and only one to ‘undeveloped and semi-civilised countries’. Training Regulations of 1934 also presents sophisticated albeit general combined arms procedures. The authors anticipated that large scale collective training through formations would cultivate an understanding of the principles they presented.

[27] French (2006) p. 37.

[28] A British Corps was comprised of approximately 39,000 men (Mike Chappell and Martin Brayley, British Army 1939–45 (1): North-West Europe, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2001, p. 17). In contrast, the BEF of 1939 was approximately 322,000 strong; see Correlli Barnett, Britain and Her Army(London: Penguin, 1970 pp. 430–431).

[29] French (2006) p. 43.

[30] Minute 1244 of the Small Arms Committee, 26 October 1932.

[31] See Tom Dugelby, The Bren Gun Saga(London: Collector Grade Publications, 1986).

[32]Routledge (1994) p. 50.

[33]Falla (1994) p. 279.

[34] French (2006) p. 45.

[35]Duncan (1970).

[36] It was as a result of large exercises that Heinz Guderian (as Chief-of-Staff in the Inspectorate of Motorised Troops) insisted on comprehensive communications installations as an essential ingredient of a blitzkrieg.